-40%

1863 CIVIL WAR ANTI-EMANCIPATE PA GETTYSBURG UNION CAPTAIN CONGRESS VP CANDIDATE

$ 63.35

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

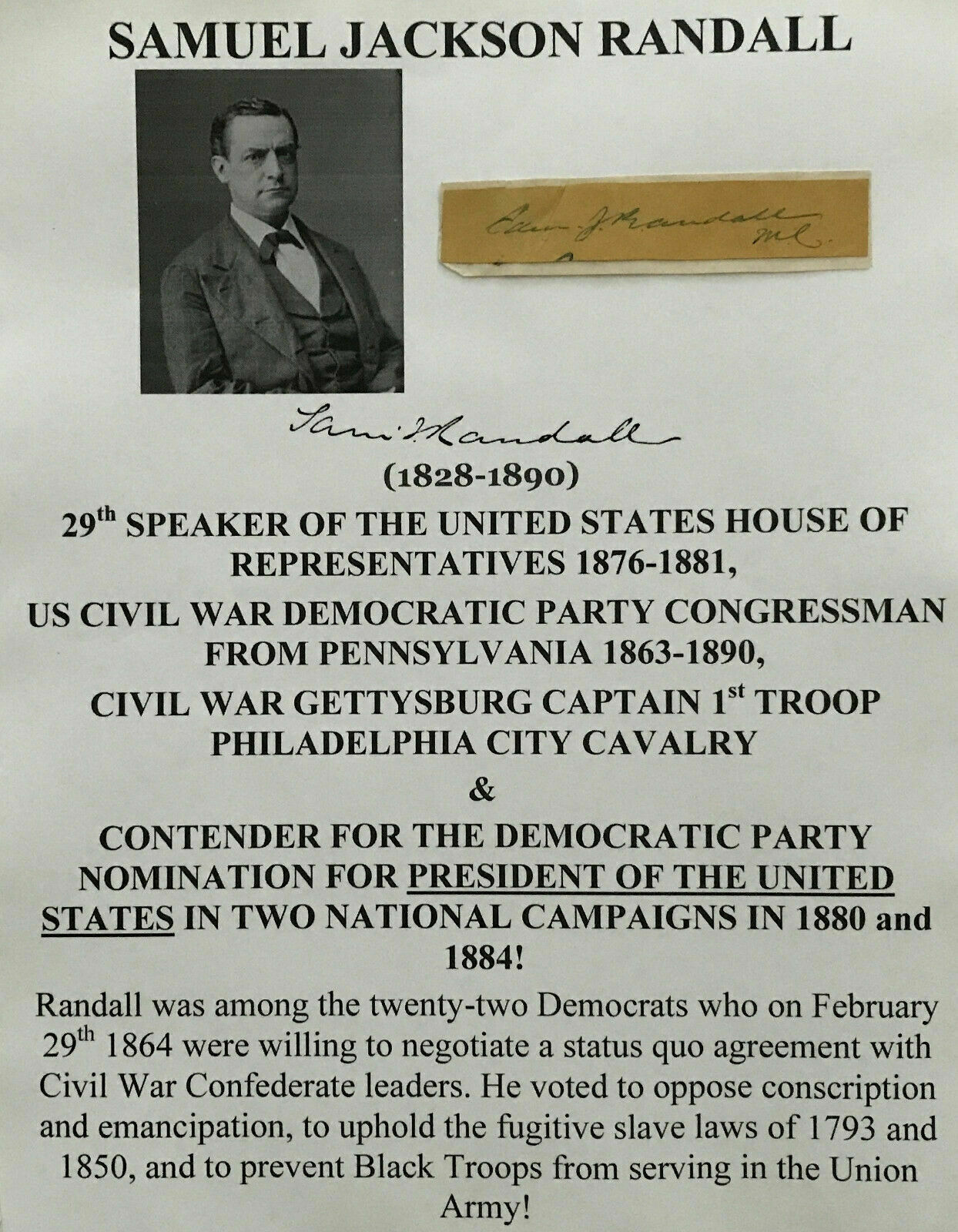

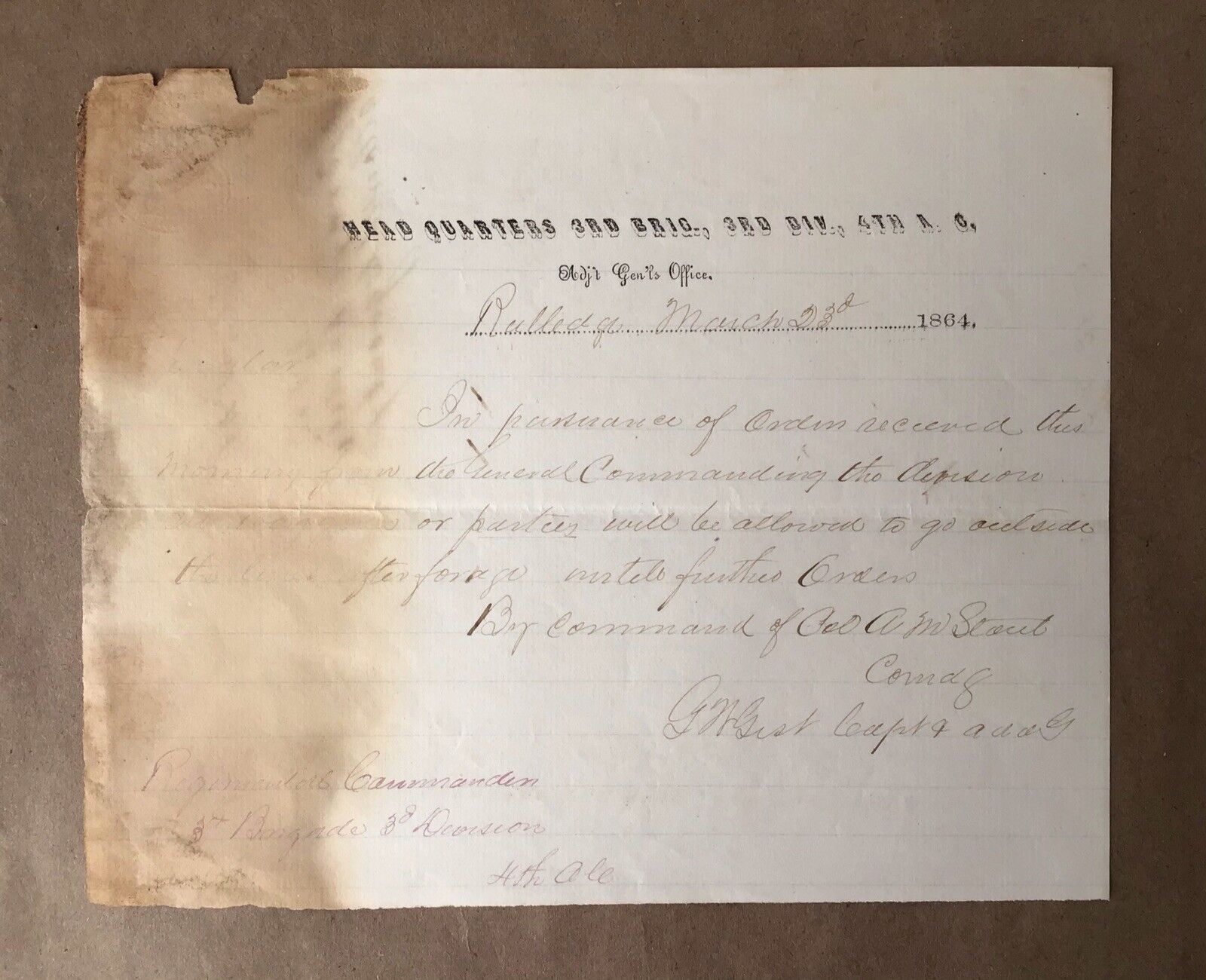

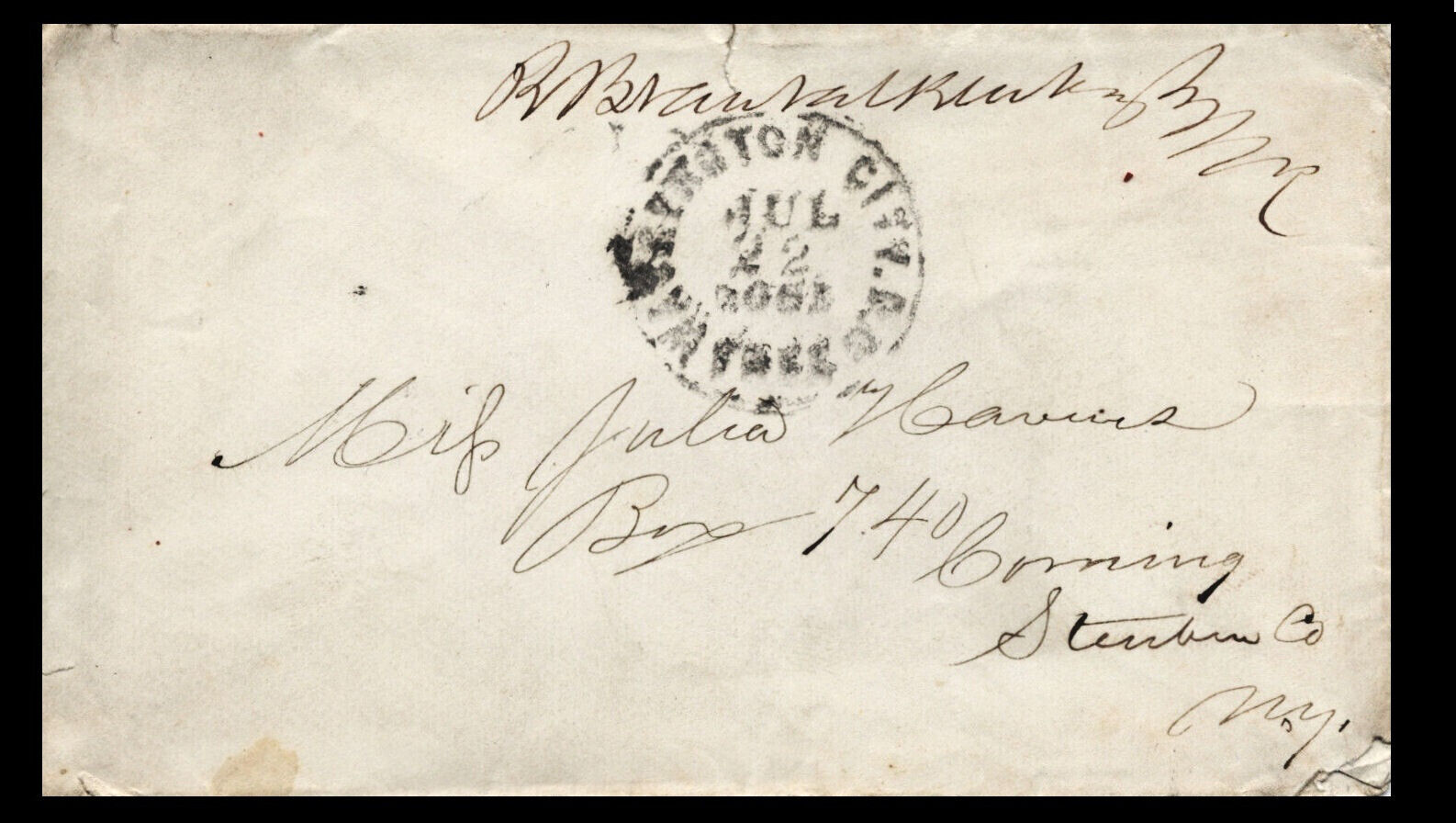

INVREF#CL4-34SAMUEL JACKSON RANDALL (1828-1890) 29th SPEAKER OF THE UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 1876-1881, US CIVIL WAR DEMOCRATIC PARTY CONGRESSMAN FROM PENNSYLVANIA 1863-1890, CIVIL WAR GETTYSBURG CAPTAIN 1st TROOP PHILADELPHIA CITY CAVALRY & CONTENDER FOR THE DEMOCRATIC PARTY NOMINATION FOR PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES IN TWO NATIONAL CAMPAIGNS IN 1880 and 1884! Randall was among the twenty-two Democrats who on February 29th 1864 were willing to negotiate a status quo agreement with Civil War Confederate leaders. He voted to oppose conscription and emancipation, to uphold the fugitive slave laws of 1793 and 1850, and to prevent Black Troops from serving in the Union Army! HERE’S RANDALL’S SIGNATURE REMOVED FROM A 19th CENTURY FREE FRANK COVER AND SIGNED: “Saml J. Randall MC~” The document measures 3¾” x ¾” and is in VERY GOOD+ CONDITION. A FINE ADDITION TO YOUR CIVIL WAR MILITARY, POLITICAL & PRESIDENTIAL HISTORY AUTOGRAPH, MANUSCRIPT & EPHEMERA COLLECTION! BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH OF THE HONORABLE SAMUEL J. RANDALL Randall, Samuel Jackson (10 Oct. 1828-13 Apr. 1890), Civil War era politician, attorney, soldier, prominent Democratic member of the United States house of Representatives and 33rd Speaker of the House of Representatives. Randall was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the son of Josiah Randall, a lawyer and local Whig politician, and Ann Worrell, the daughter of a leading Philadelphia Jeffersonian Republican. Randall attended the University Academy in that city and went to work at the age of seventeen in the counting room of a silk merchant. He then became a partner in a coal business and at twenty-one formed a partnership to deal in odd-lot iron. In 1851 he married Fannie Agnes Ward (whose father had been a Democratic congressman from New York); they had three children. Born and married into politically active families, Randall quickly entered rough-and-tumble Philadelphia politics, where he used "his fists as well as his head" (Alexander, p. 129). Apparently attracted by xenophobia, Randall ran for the Philadelphia Common Council as an American (anti-foreign) Whig and served from 1852 to 1856. When the Whig party began disintegrating, Randall and his father (who was a friend of James Buchanan) moved into the Democratic party. From 1858 to 1860 he served as a Democrat in the Pennsylvania Senate, where he was on the committee on retrenchment and reform. He made his mark, however, by securing charters for Philadelphia street railway companies and, aware of the high cost of financing such ventures, by attacking banks for their exorbitant rates. When the Civil War broke out, Randall served for ninety days in 1861 and for a short time during the 1863 Gettysburg campaign without seeing any action. In 1862, prior to that campaign, Randall had been elected as a Democrat to Congress. The Republicans, to carry other congressional seats, had gerrymandered his constituents, most of whom labored on the waterfront or in shops and factories, into an overwhelmingly Democratic district. They reelected Randall thirteen times and he served from 1863 until his death. Believing that the Civil War's objective was to preserve both the Constitution and the Union without disturbing slavery, Randall was among the twenty-two Democrats who on 29 February 1864 were willing to negotiate a status quo antebellum with Confederate leaders. In April 1864 he also refused to join War Democrats and Republicans in censuring or declaring unworthy two Peace Democrats who supported the Confederacy in the House of Representatives. During the war Randall voted to oppose conscription and emancipation; to uphold the fugitive slave laws of 1793 and 1850; and to prevent blacks from serving in the army, voting in the territory of Montana, and riding on streetcars in the District of Columbia. As the war drew to a close, Randall and his fellow Democrats argued that the Union did not need to be reconstructed because it had not been dissolved and that the suppression of the rebellion in a state automatically restored its rights under the Constitution. He opposed, without success, Republican-backed constitutional amendments and legislation that required the governments of states that had joined the Confederacy to guarantee freedom, civil rights, and the vote to African Americans. Although neither imposing in figure nor stylish in dress, Randall's attentiveness, "terse, withering sentences," and "scornful invective" (Alexander, p. 240), delivered in a high, shrill voice, made him a formidable debater and a party leader. His mastery of obstruction was so great that it was called "Samrandallism." In January 1875 dilatory motions, requiring time-consuming roll calls, delayed civil rights legislation, keeping the House in continuous session forty-six and a half hours, and in February he led a 72-hour filibuster, preventing passage of a companion enforcement bill that would have renewed the power of the president to suspend the writ of habeas corpus. When not opposing Reconstruction measures, Randall hampered Republicans by sponsoring amnesty legislation for those who supported the Confederacy, by trying to pare down appropriations bills, by opposing land grants for railroad construction and mail subsidies for steamship companies, by pressing for investigations of Credit Mobilier and Sanborn contract corruption, by emphasizing President Ulysses S. Grant's disastrous second term (through the advocacy of a single six-year term for the president), and by trying to identify the Democrats with retrenchment and reform. As an old Philadelphia Whig, Randall was a protectionist and, to keep the nation dependent on the tariff, opposed the income tax and most excise taxes. Following the Democratic victory in the 1874 election, Randall angled to become Speaker of the incoming House of Representatives. Although he was a hard-money man for whom full payment of the Civil War debt was a sacred obligation, he flirted with the soft-money men by advocating that the 0 million in banknotes issued by national banks be replaced with greenbacks and by opposing the 1875 act that called for the resumption in 1879 of specie payments for greenbacks. In 1875, by coupling antiresumption with pro-reform, he wrested control of the Pennsylvania Democratic party from pliant politicians identified with the Pennsylvania Railroad. He also campaigned in Ohio for the soft-money Democratic gubernatorial candidate and secured the support of the Ohio delegation for the Speakership. But he lost the friendship of the hard-money men, and by championing the retroactive Salary Grab Act (1873), he tarnished his retrenchment and reform image. In December 1875 he lost to Michael Kerr of Indiana, a hard-money man who had refused to collect his back pay. When Kerr died in August 1876, Randall mended fences with eastern hard-money men and cultivated Samuel J. Tilden, the 1876 Democratic presidential nominee. When Congress reassembled in December during the crisis over the disputed presidential election, the Democratic majority named Randall the Speaker of the House. With Tilden remaining aloof from the struggle, Randall, who commanded the only branch of the federal government controlled by the Democratic party, became its de facto leader. His objective was to elect Tilden, but when that failed he worked to force Republicans to concede home rule (white supremacy Democratic governments) in the South and to hold his party together in the House (assuring his reelection as Speaker in the next Congress). To achieve these ends Randall fluctuated between moderation and extremism, as he and his party first compromised, then threatened to plunge the nation into chaos by delaying the counting of electoral votes, and finally at the last moment accepted the election of the Republican candidate, Rutherford B. Hayes. Indeed, Randall was the crucial figure in the disputed election crisis. His committee appointments and his support made the compromise Electoral Commission Act (1877) possible. His rulings, after the commission began to award disputed states to Hayes, allowed the House to recess and delay the count but not reject the commission's decisions. His intemperate remarks in the Democratic caucus both frightened Republicans (with the threat of a filibuster that would force a new presidential election) and panicked southern Democrats (with the threat of dire consequences should they desert to the Republicans to secure home rule). And finally his refusal to entertain dilatory motions of filibusterers enabled Hayes to be inaugurated on schedule. "To me," he later explained, the [Electoral Commission] law was higher than the rules [of the House] when the law came in conflict with the rules" (Follett, p. 123). Although James G. Blaine, a Republican predecessor as Speaker of the House, remarked that Randall never neglected his public duties and never forgot the interests of the Democratic party, Randall's subsequent moves as Speaker united the Republicans and damaged the Democrats. He supported the Clarkson N. Potter investigation into allegations of Republican fraud in the 1876 election, and he backed attempts to repeal the election laws (designed to protect voting rights under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments) by attaching riders to appropriations bills. Both strategies were failures. The Potter committee uncovered nothing damaging to the Republicans, but by confirming that Tilden's nephew had tried to buy the election for his uncle, it destroyed both Tilden's candidacy and the fraud issue for 1880. By vetoing appropriations bills with riders, Hayes prevented Congress from encroaching on the executive's lawmaking power and rallied Republicans with his stirring defense of voting rights. In the 1880 election the Republicans carried the presidency and the House of Representatives, and Randall ceased to be Speaker in 1881. As Speaker, Randall exercised great power. He disagreed with the low tariff attitudes of most Democrats and was accused of being too intimate with lobbyists as he stacked committees and made rulings that retained protective tariffs on American manufactures. Led by him the House in 1880 condensed 166 rules into 45 that fostered "order, accuracy, uniformity, and economy of time" (Alexander, p. 195). The new rules enhanced the control of the Speaker by converting the House Rules Committee into a powerful standing committee, which the Speaker chaired. Increasingly out of step with his party on the tariff issue, Randall was not named Speaker when in 1883 the Democrats regained the House. But as the powerful chair of the Appropriations Committee, he reduced expenditures and controlled legislation requiring funding. In 1884 and 1886 Randall was instrumental in defeating tariff reduction bills proposed by his fellow Democrat and archrival William R. Morrison. In 1888, however, President Grover Cleveland deprived Randall of federal patronage in Pennsylvania and with it the control of that state's Democratic Party because Randall had opposed the administration-backed Mills tariff bill. Despite these losses and the ravages of colon cancer, Randall remained a parsimonious, partisan leader of House Democrats until he died in Washington. "There may have been better parliamentarians, men of broader intellect and more learning," Republican Speaker of the House Thomas B. Reed remarked, "but there have been few men with a will more like iron or a courage more unfaltering" (House, p. 135). Bibliography The Randall papers are in the Van Pelt Library of the University of Pennsylvania. See Albert Virgil House, Jr., "The Political Career of Samuel Jackson Randall" (Ph.D. diss., Univ. of Wisconsin, 1934), for the most complete study of Randall. See also Mary Parker Follett, The Speaker of the House of Representatives (1902); De Alva Stanwood Alexander, History and Procedure of the House of Representatives (1916); and George B. Galloway, History of the House of Representatives (1961; rev. ed. 1976). An obituary is in the New York Times, 14 Apr. 1890. [Source: American National Biography] PROVENANCE OF ORIGIN PURCHASE HISTORY Proud member of the Universal Autograph Collectors Club (UACC), The Ephemera Society of America, the Manuscript Society & the American Political Items Collectors (APIC) (member name: John Lissandrello). I subscribe to each organizations' code of ethics and authenticity is guaranteed. ~Providing quality service & historical memorabilia online for over twenty years!