-40%

CIVIL WAR CADET BLAIR CDV PHOTO ALEXANDER GARDNER FULL STANDING UNIFORM IMAGE VF

$ 21.11

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

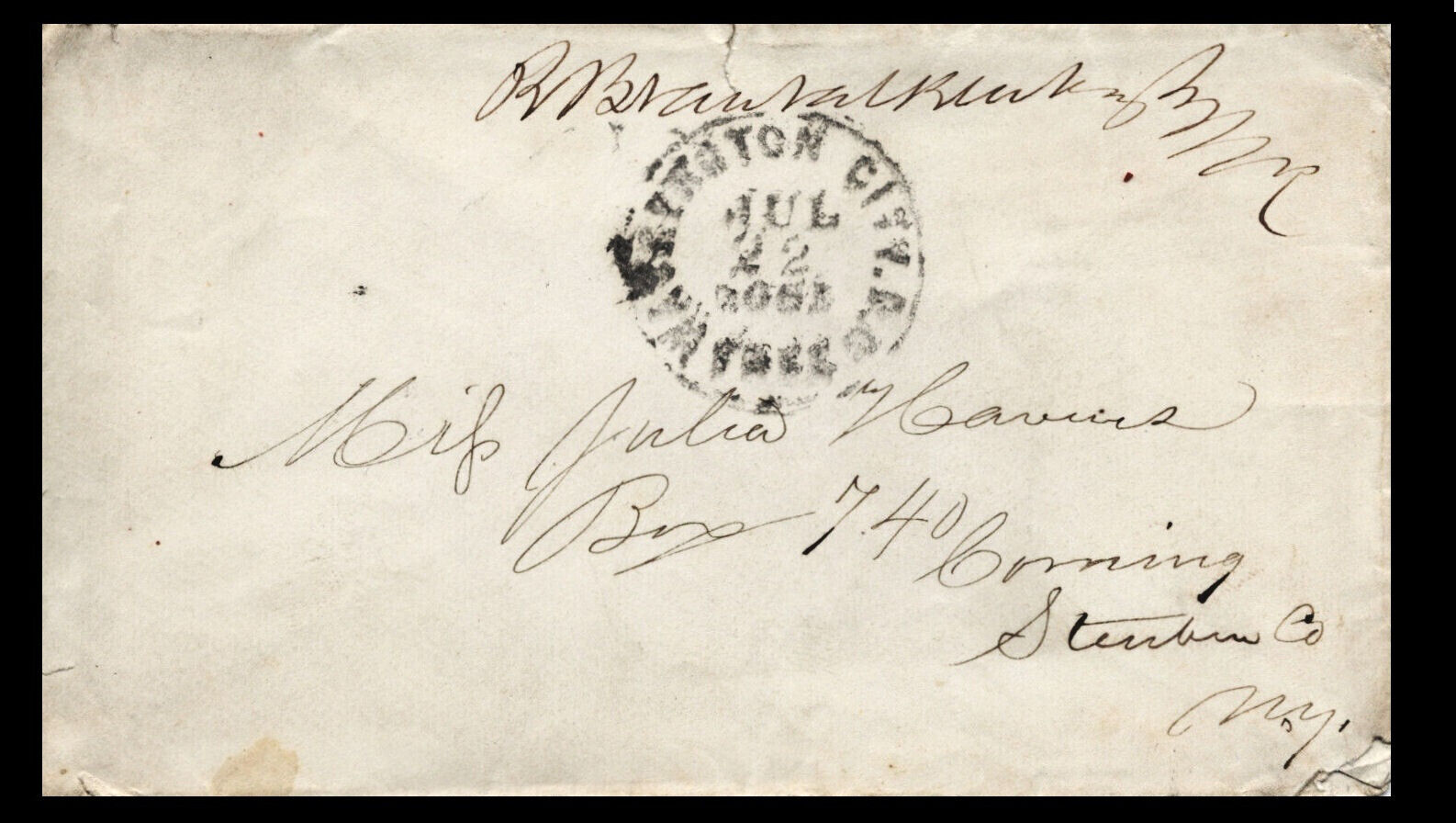

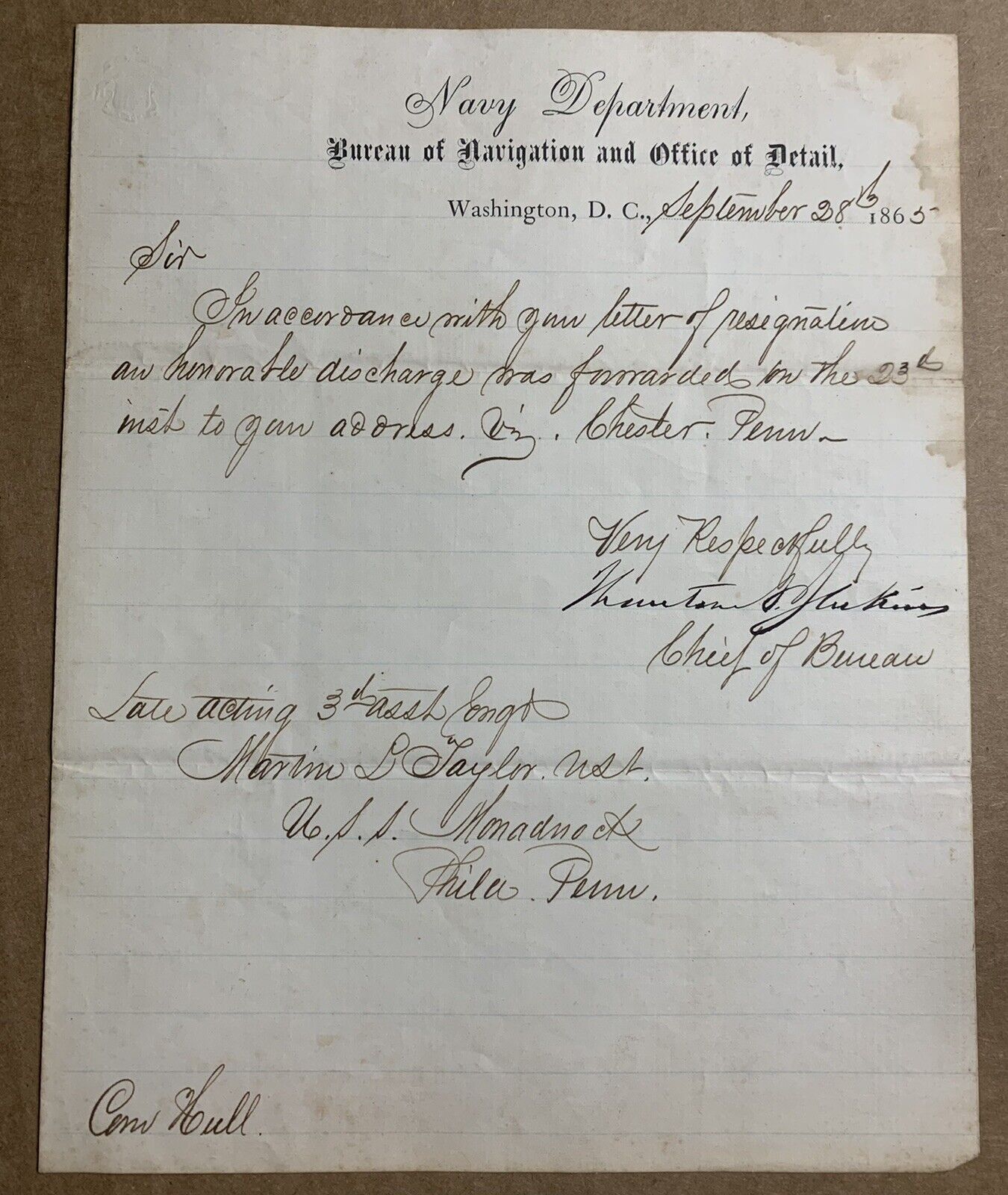

HERE’S ARARE and VERY FINE “GARDNER

” MILITARY CARTE-DE-VISITE (

CDV

) PHOTOGRAPH OF A VERY YOUNG CIVIL WAR CADET “

BLAIR

”

AN FULL-STANDING PHOTOGRAPHIC IMAGE OF A CADET IN FULL UNIFORM.

THE VERSO BEARS THE FAMOUS PHOTOGRAPHER’S BACKMARK OF:

“GARDNER, PHOTOGRAPHER,

511 Seventh street and 332 Penna. Avenue.”

~.

“PUBLISHED BY PHILIP & SOLOMONS,

WASHINGTON, D.C.

”

The front and verso bear pencil notations indicating that the image is that of a man named “Blair” – Further research needed!

SEVERAL WORKS BY PHOTOGRAPHIC ARTIST ALEXANDER GARDNER OF THE CIVIL WAR ARE HIGHLY PRIZED

!

GARDNER INITIALLY TRAINED WITH MATHEW BRADY, BEFORE HE WENT OUT ON HIS OWN!

The CDV photo measures

2½”

x

4”

and is in VF+ condition.

ALEXANDER GARDNER and HIS PHOTOGRAPHY STUDIO

Alexander Gardner

(October 17, 1821 – December 10, 1882) was a Scottish photographer who immigrated to the United States in 1856, where he began to work full-time in that profession. He is best known for his photographs of the

American Civil War

,

U.S. President

Abraham Lincoln

, and of the conspirators and the execution of the participants in the

Lincoln assassination

plot.

Civil War photography

Abraham Lincoln became the President of the United States in the

November 1860 election

and along with his election came the threat of war. Gardner was well-positioned in Washington, D.C. to document the pre-war events, and his popularity rose as a portrait photographer, capturing the visages of soldiers leaving for war.

Mathew Brady shared his idea with Gardner about photographing the Civil War. Gardner's relationship with

Allan Pinkerton

, chief of the intelligence operation that would become the

Secret Service

), was central to promoting Brady's idea to Lincoln. Pinkerton recommended Gardner for the position of chief photographer under the jurisdiction of the

U.S. Topographical Engineers

. Following that short appointment, Gardner became a staff photographer under General

George B. McClellan

, commander of the

Army of the Potomac

. At this point, Gardner's management of Brady's gallery ended. The honorary rank of captain was bestowed upon Gardner, and he photographed the

Battle of Antietam

in September 1862, developing photos in his travelling darkroom. Gardner's photography was so detailed that relatives could identify their loved ones by their facial features in his images.

Gardner's work has often been misattributed to Brady, and despite his considerable output, historians have tended to give Gardner less than full recognition for his documentation of the Civil War. When Lincoln relieved McClellan from command of the Army of the Potomac in November 1862, Gardner’s role as chief army photographer diminished. About this time, Gardner ended his working relationship with Brady, probably in part because of Brady's practice of attributing his employees' work as "Photographed by Brady".That winter, Gardner followed General

Ambrose Burnside

, photographing the

Battle of Fredericksburg

. Next, he followed General

Joseph Hooker

. In May 1863, Gardner and his brother James opened their own studio in Washington, D.C., hiring many of Brady's former staff. Gardner photographed the

Battle of Gettysburg

(July 1863) and the

Siege of Petersburg

(June 1864–April 1865) during this time.

In 1866, Gardner published a two-volume work,

Gardner's Photographic Sketch Book of the Civil War

. Each volume contained 50 hand-mounted original prints. The book did not sell well.

[7]

Not all photographs were Gardner's; he credited the negative producer and the positive print printer. As the employer, Gardner owned the work produced, as with any modern-day studio. The sketchbook contained work by

Timothy H. O'Sullivan

, James F. Gibson, John Reekie,

William Pywell

, James Gardner (his brother),

John Wood

,

George N. Barnard

, David Knox and

David Woodbury

, among others. Some of his photographs of Lincoln were considered to be the last taken of the President, four days before his assassination, although later this claim was found to be incorrect; the pictures were actually taken in February 1865, the last one on February 5.Gardner would photograph Lincoln on a total of seven occasions while Lincoln was alive. He also documented Lincoln's funeral, and photographed the conspirators involved (with

John Wilkes Booth

) in Lincoln's assassination. Gardner was the only photographer allowed at their execution by hanging, photographs of which would later be translated into

woodcuts

for publication in

Harper's Weekly

.

Post-War

After the war, Gardner was commissioned to photograph

Native Americans

who came to Washington to discuss treaties; and he surveyed the proposed route of the

Kansas Pacific railroad

to the Pacific Ocean. Many of his photos were

stereoscopic

. After 1871, Gardner gave up photography and helped to found an insurance company. Gardner stayed in Washington until his death. When asked about his work, he said, "It is designed to speak for itself. As mementos of the fearful struggle through which the country has just passed, it is confidently hoped that it will possess an enduring interest." He became sick in the late fall of 1882 and died shortly afterward on December 10, 1882, at his home in Washington, D.C. He was survived by his wife and two children. He was buried in local

Glenwood Cemetery

.

In 1893, photographer J. Watson Porter, who had worked for Gardner years before, tracked down hundreds of glass negatives made by Gardner, that had been left in an old house in Washington where Gardner had lived. The result was a story in the

Washington Post

and renewed interest in Gardner's photographs.

Controversy

A century later, photographic analysis suggested that Gardner had manipulated the setting of at least one of his Civil War photos by moving a soldier's corpse and weapon into more dramatic positions. In 1961, Frederic Ray of the

Civil War Times

magazine compared several of Gardner's Gettysburg photos showing "two" dead Confederate snipers and realized that the same body had been photographed in two separate locations. One of his most famous images, "Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter", has been argued to be a fabrication. This argument, first put forth by William Frassanito in 1975, goes this way: Gardner and his assistants Timothy O'Sullivan and James Gibson had dragged the sniper's body 40 yards (37 m) into the more photogenic surroundings of the

Devil's Den

to create a better composition. Though Ray's analysis was that the same body was used in two photographs, Frassanito expanded on this analysis in his 1975 book

Gettysburg: A Journey in Time

, and acknowledged that the manipulation of photographic settings in the early years of photography was not frowned upon.

I am a proud member of the Universal Autograph Collectors Club (UACC), The Ephemera Society of America, the Manuscript Society and the American Political Items Collectors (APIC) (member name: John Lissandrello). I subscribe to each organizations' code of ethics and authenticity is guaranteed. ~Providing quality service and historical memorabilia online for over 20 years.~

WE ONLY SELL GENUINE ITEMS, i.e., NO REPRODUCTIONS, FAKES OR COPIES!