-40%

CIVIL WAR GETTYSBURG GENERAL SENATOR MO DIPLOMAT INTERIOR SCHURZ LETTER SIGNED !

$ 5.53

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

CARL SCHURZ(1829 – 1906)

CIVIL WAR BATTLE OF GETTYSBURG and CHANCELLORSVILLE UNION MAJOR GENERAL 1862-65,

STATESMAN-UNITED STATES MINISTER TO SPAIN APPOINTED BY PRESIDENT LINCOLN IN 1861,

US REPUBLICAN PARTY SENATOR FROM MISSOURI – THE 1

st

GERMAN-BORN AMERICAN ELECTED TO THE US SENATE 1869-75,

13

th

UNITED STATES SECRETARY OF THE INTERIOR APPOINTED BY PRESIDENT HAYES and GARFIELD 1877-1881,

GERMAN REVOLUTIONARY 1848-1849

&

ACCOMPLISHED JOURNALIST, NEWSPAPER EDITOR, ORATOR & REFORMER!

<

<>

>

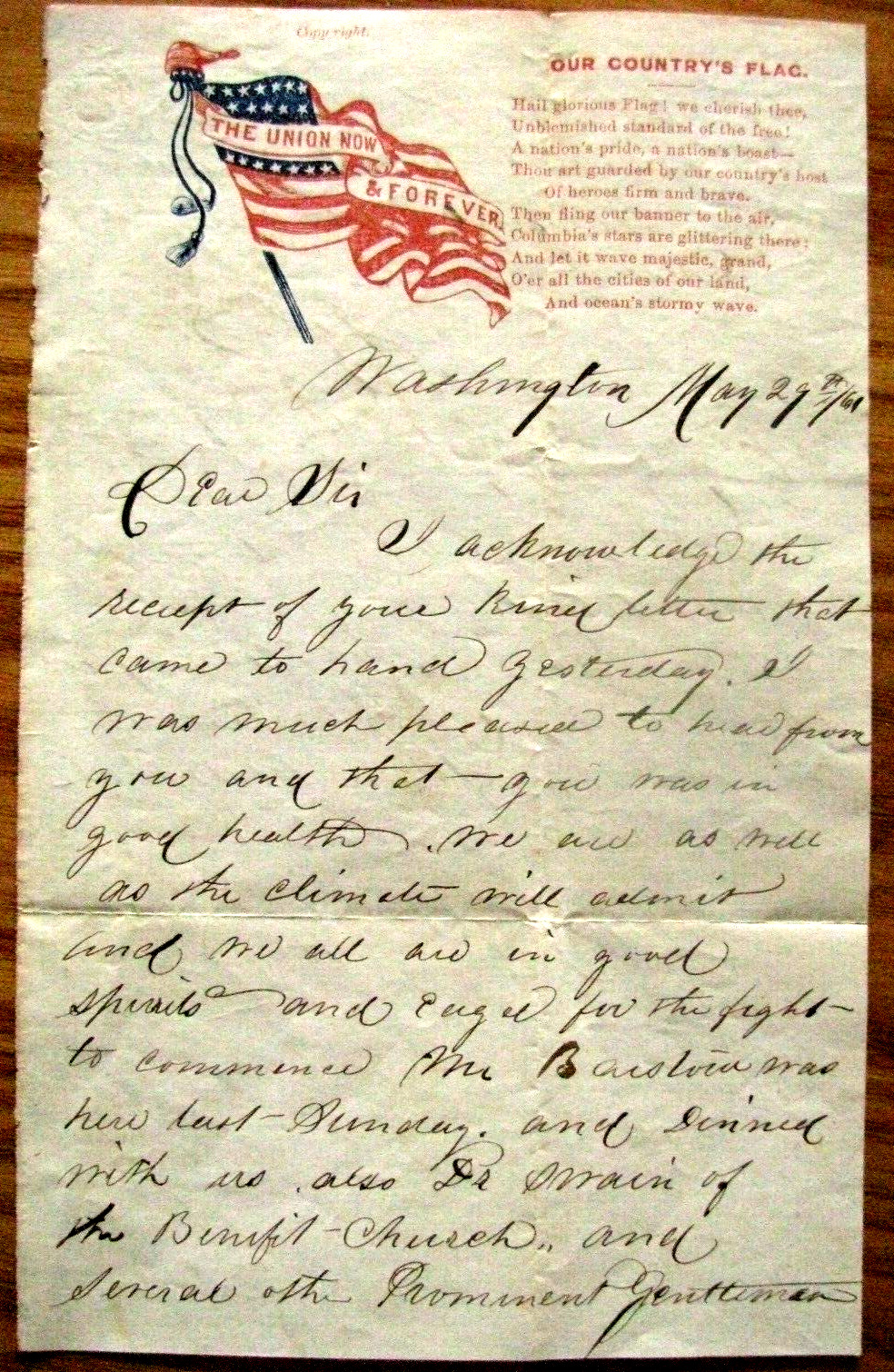

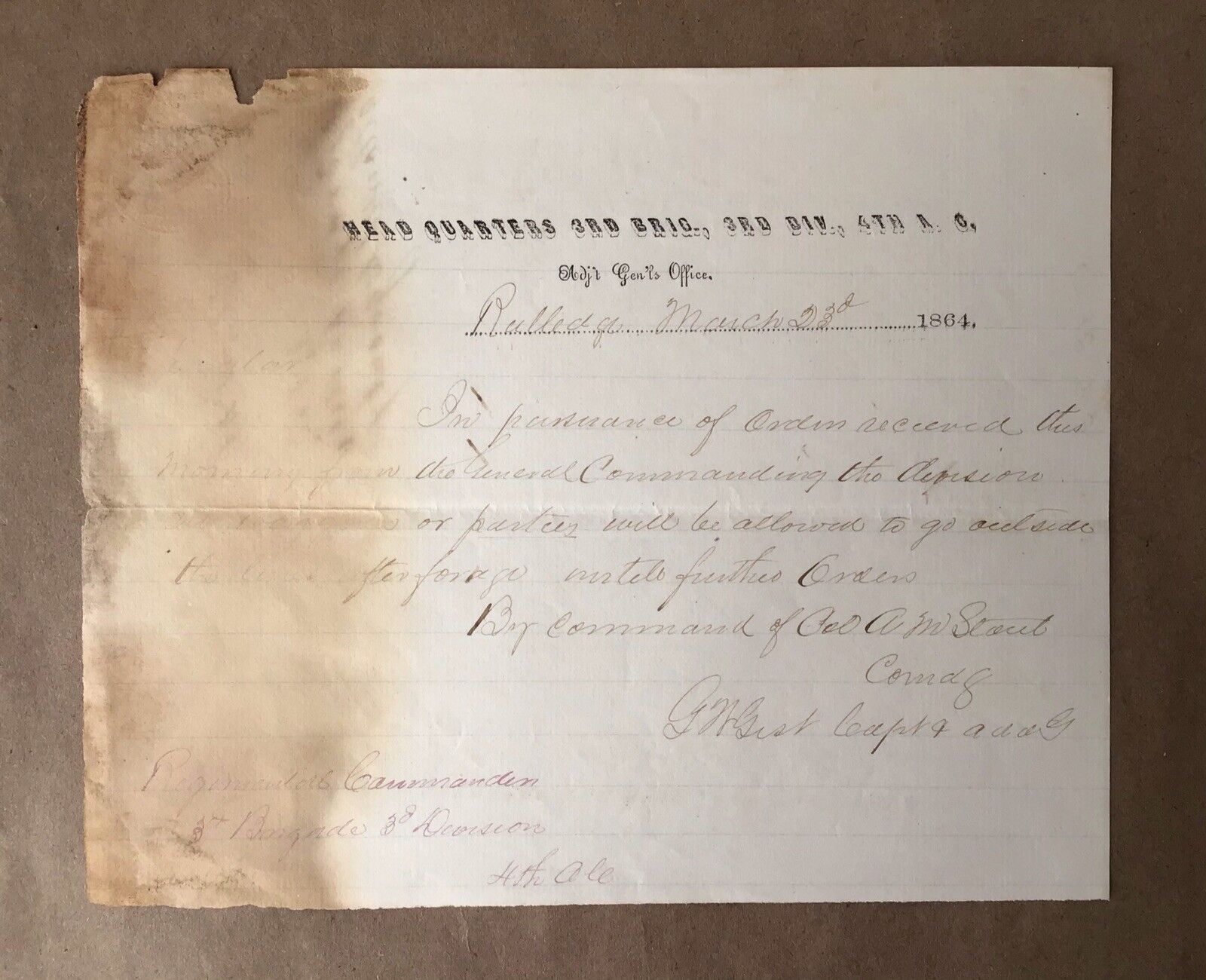

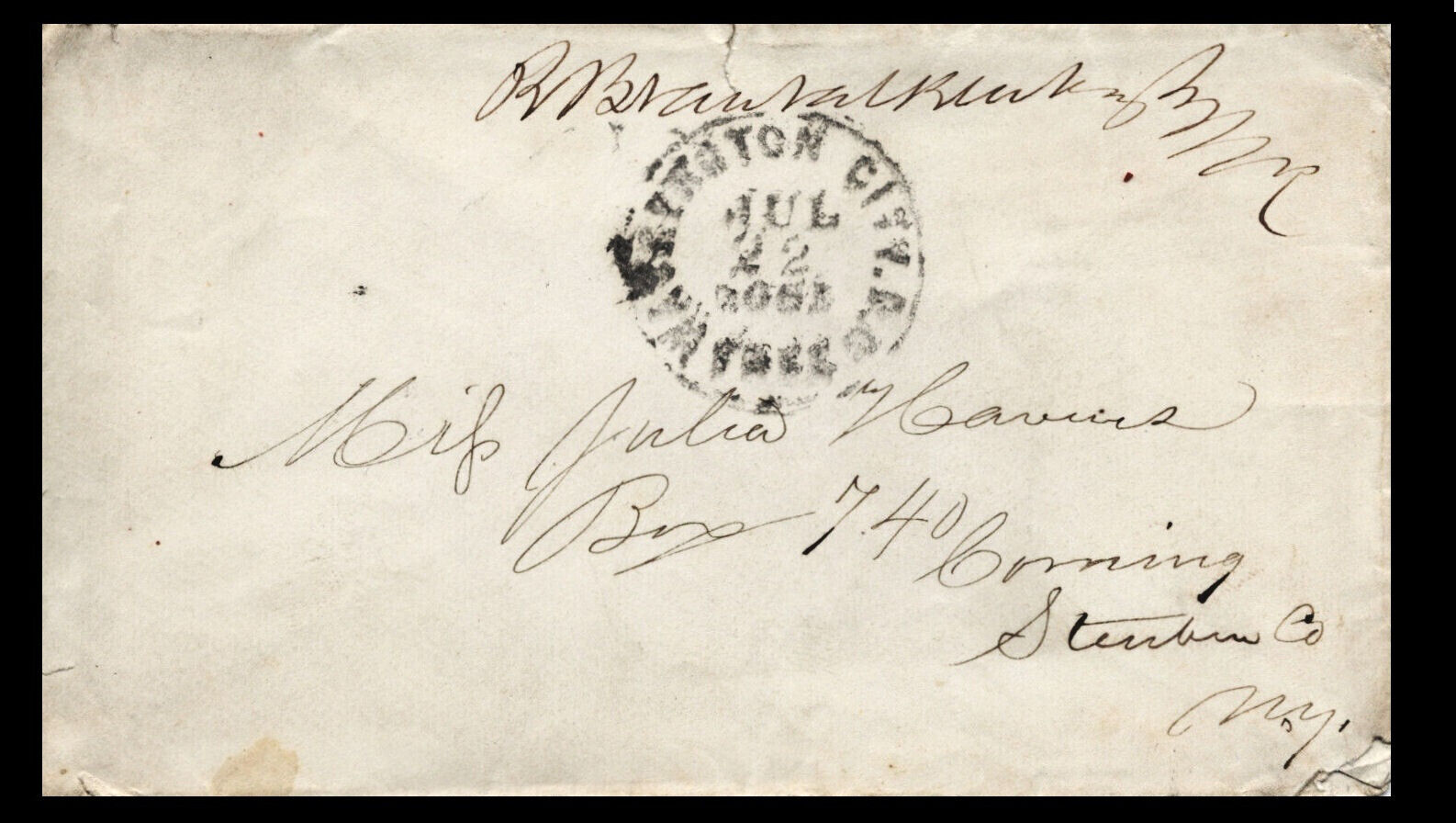

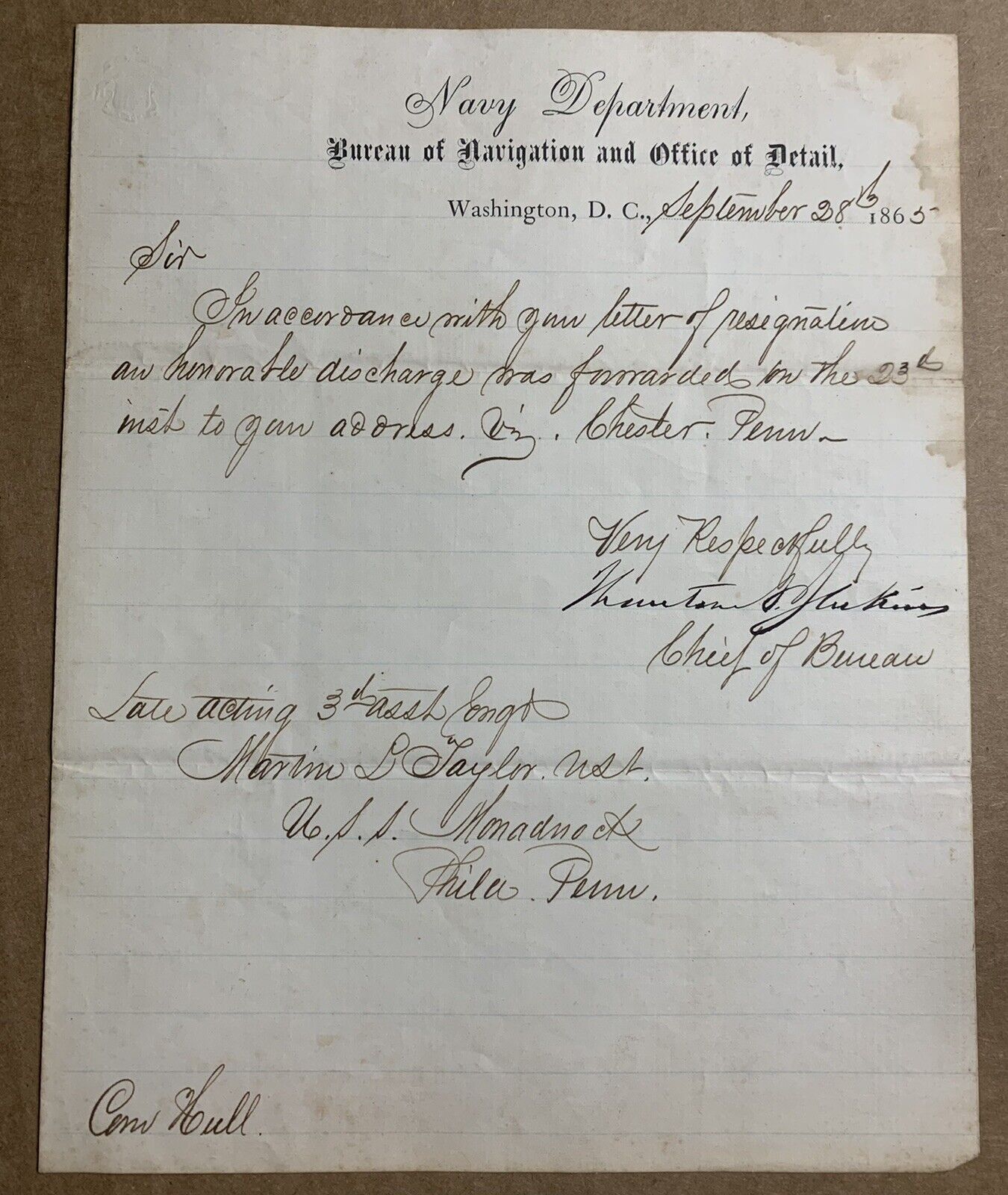

HERE’S AN AUTOGRAPH LETTER SIGNED BY SCHURZ ABOUT ‘

MISSING MAIL

,’ 1p., FRONT and VERSO, APRIL 10, 1886, NEW YORK,

TO

ABRAM STEVENS HEWITT

(1822 - 1903)

U.S. DEMOCRATIC PARTY CONGRESSMAN FROM NEW YORK 1870s-1880s,

87

th

MAYOR OF NEW YORK CITY 1887-1888,

AIDED IN OVERTHROWING THE “BOSS” TWEED RING

&

MILLIONAIRE IRON MANUFACTURER, INDUSTRIALIST and PHILANTHROPIST.

IN PART:

“Yesterday the letter carrier brought me an empty wrapper bearing your frank, informing me that it had arrived at the post office in that condition….may I trouble you for the same…documents again? And is there a way of getting a copy of the report of the Labor Commissioners?

If I am taxing your kindness too much, you must let me know…”

BOLDLY EXECUTED & SIGNED BY SCHURZ!

The document measures 4¾” x 6” and is in very finr condition.

<

<>

>

BIOGRAPHY OF CIVIL WAR MAJOR GENERAL

CARL SCHURZ

Carl Christian Schurz

(1829–1906) was a

German

revolutionary,

American

statesman and reformer, and

Union Army

Major

General

in the

American Civil War

. He was also an accomplished journalist, newspaper editor and orator, who in 1869 became the first

German-born American

elected to the

United States Senate

.

His wife,

Margarethe Schurz

, was instrumental in establishing the

kindergarten

system in the United States.

During his later years, Schurz was perhaps the most prominent independent in American politics, noted for his high principles, his avoidance of political partisanship, and his moral conscience.

[3]

He is famous for saying: "

My country, right or wrong

; if right, to be kept right; and if wrong, to be set right."

[4]

Many streets, schools, and parks are named in honor of him, including

New York City

's

Carl Schurz Park

.

Early life

Schurz was born in Liblar (now part of

Erftstadt

),

Germany

on March 2, 1829, the son of a schoolteacher. He studied at the

Jesuit Gymnasium

of

Cologne

, and learned piano under private instructors. Financial problems in his family obligated him to leave school a year early, without graduating, to help manage his family's financial affairs. Later he graduated from the

gymnasium

by passing a special examination, and he entered the

University of Bonn

.

At Bonn, he developed a friendship with one of his professors,

Gottfried Kinkel

. He joined the nationalistic

Studentenverbindung

Burschenschaft

Franconia at Bonn, which at the time included among its members

Friedrich von Spielhagen

,

Johannes Overbeck

,

Julius Schmidt

, Carl Otto Weber,

Ludwig Meyer

and

Adolf Strodtmann

.

[5]

This fraternity experience led to his joining the

Phi Kappa Psi

Fraternity at Cornell University

[6]

sponsored by his former comrade-in-arms,

Joseph Benson Foraker

.

In response to the early events of the

revolutions of 1848

, Schurz and Kinkel founded the

Bonner Zeitung

, a paper advocating democratic reforms. At first Kinkel was the editor and Schurz a regular contributor. These roles were reversed when Kinkel left for Berlin to become a member of the Prussian Constitutional Convention.

[7]

When the

Frankfurt rump parliament

called for people to take up arms in defense of the new German constitution, Schurz, Kinkel, and others from the University of Bonn community did so. During this struggle, Schurz became acquainted with

Franz Sigel

,

Alexander Schimmelfennig

,

Fritz Anneke

,

Friedrich Beust

,

Ludwig Blenker

and others, many of whom he would meet again in the Union Army during the U.S. Civil War.

During the 1849 military campaign in Palatinate and Baden, Schurz was adjunct officer of the commander of the artillery,

Fritz Anneke

, who was accompanied on the campaign by his wife,

Mathilde Franziska Anneke

. The Annekes would later move to the U.S., where each became

Republican Party

supporters. Anneke's brother,

Emil Anneke

, was a founder of the Republican party in Michigan.

Fritz Anneke achieved the rank of

colonel

and became the commanding officer of the

34th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry Regiment

during the Civil War; Mathilde Anneke contributed to both the

abolitionist

and

suffrage movements

of the United States.

The revolution in Germany ultimately failed. When the fortress at

Rastatt

, the last holdout, surrendered with Schurz inside, Schurz escaped to

Zürich

. In 1850, he returned secretly to Prussia, rescued Kinkel from prison at

Spandau

and helped him to escape to

Edinburgh, Scotland

. Schurz then went to

Paris

, but the police forced him to leave France on the eve of the

coup d'état of 1851

, and he moved to

London

. Remaining there until August 1852, he made his living by teaching the

German language

. He married fellow revolutionary

Johannes Ronge

's sister-in-law,

Margarethe Meyer

, in July 1852 and then moved to America. Living initially in

Philadelphia

,

Pennsylvania

, the Schurzes moved to

Watertown, Wisconsin

, where Carl nurtured his interests in politics and Margarethe began her seminal work in early childhood education. Schurz is probably the best known of the

Forty-Eighters

, the German

emigrants

who came to the United States after the failed liberal revolutions.

Politics in the United States

In 1855, Schurz settled in

Watertown, Wisconsin

, where he immediately became immersed in the anti-slavery movement and in politics, joining the

Republican Party

. In 1857, he was an unsuccessful Republican candidate for lieutenant-governor. In the

Illinois

campaign of the next year between

Abraham Lincoln

and

Stephen A. Douglas

, he took part as a speaker on behalf of Lincoln—mostly in

German

—which raised Lincoln's popularity among German-American voters (though it should be remembered that Senators were not directly elected in 1858, the election being decided by the Illinois General Assembly). Later, in 1858, he was admitted to the Wisconsin

bar

and began to

practice law

in

Milwaukee

. In the state campaign of 1859, he made a speech attacking the

Fugitive Slave Law

, arguing for

states' rights

. In

Faneuil Hall

,

Boston

, on April 18, 1859,

[8]

he delivered an oration on "True Americanism," which, coming from an alien, was intended to clear the Republican party of the charge of "

nativism

". Wisconsin Germans unsuccessfully urged his nomination for governor in 1859. In the

1860 Republican National Convention

, Schurz was spokesman of the delegation from Wisconsin, which voted for

William H. Seward

; despite this, Schurz was on the committee which brought Lincoln the news of his nomination.

Civil War

In spite of Seward's objection, grounded on Schurz's European record as a revolutionary, Lincoln sent him in 1861 as

ambassador to Spain

. He succeeded in quietly dissuading Spain from supporting the South. Persuading Lincoln to grant him a commission in the Union army, Schurz was commissioned

brigadier general

of Union volunteers in April, and in June took command of a division, first under

John C. Frémont

, and then in

Franz Sigel

's corps, with which he took part in the

Second Battle of Bull Run

. He was promoted

major general

of volunteers on March 14 and was a

division

commander in the

XI Corps

at the

Battle of Chancellorsville

, under General

Oliver O. Howard

, with whom he later had a bitter controversy over the strategy employed at that battle, resulting in their defeat by

Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson

. He was at

Gettysburg

(a victory for the

Union

) commanding the Third Division of Howard's XI Corps, and at

Chattanooga

(also a victory for the

Union

side), at which he served with the future Senator

Joseph B. Foraker

,

John Patterson Rea

, and Luther Morris Buchwalter, brother to

Morris Lyon Buchwalter

. Senator

Charles Sumner

(R-MA) was a Congressional observer during the campaign. Later, he was put in command of a Corps of Instruction at

Nashville

. He briefly returned to active service, where in the last months of the war when he was with

Sherman

's army in

North Carolina

as chief of staff of

Henry Slocum

's

Army of Georgia

. He resigned from the army when the war ended.

Postbellum

In the summer of 1865, President

Andrew Johnson

sent Schurz through the South to study conditions; they then quarrelled because Schurz approved General

H.W. Slocum

's order forbidding the organization of militia in

Mississippi

. Schurz's report, suggesting the readmission of the states with complete rights and the investigation of the need of further legislation by a Congressional committee, was ignored by the President. In 1866, Schurz moved to Detroit, where he was chief editor of the

Detroit Post

. The following year, he moved to St. Louis, becoming editor and joint proprietor with

Emil Praetorius

of the

Westliche Post

(Western Post), where he hired

Joseph Pulitzer

as a cub reporter. In the winter of 1867-1868, he traveled in Germany – the account of his interview with

Otto von Bismarck

is one of the most interesting chapters of his

Reminiscences

. He spoke against "repudiation" (of war debts) and for "honest money" (the gold standard) during the Presidential campaign of 1868.

In 1869, he was elected to the

United States Senate

from

Missouri

, becoming the first German American in that body. He earned a reputation for his speeches, which advocated fiscal responsibility, anti-imperialism, and integrity in government. During this period, he broke with the

Grant

administration, starting the

Liberal Republican

movement in Missouri, which in 1870 elected

B. Gratz Brown

governor.

After

Fessenden's

death, Schurz was a member of the Committee on Foreign Affairs where Schurz opposed Grant's Southern policy as well as his bid to annex

Santo Domingo

. Schurz was identified with the committee's investigation of arms sales to and cartridge manufacture for the French army by the United States government during the

Franco-Prussian War

.

In 1872, he presided over the

Liberal Republican

convention, which nominated

Horace Greeley

for

President

. Schurz's own choice was

Charles Francis Adams

or

Lyman Trumbull

, and the convention did not represent Schurz's views on the tariff. Schurz campaigned for Greeley anyway. Especially in this campaign, and throughout his career as a Senator and afterwards, he was a target for the pen of

Harper's Weekly

artist

Thomas Nast

, usually in an unfavorable way.

[9]

The election was a debacle for the Greeley supporters: Grant won by a landslide, and Greeley died shortly after the election.

In 1875, he campaigned for

Rutherford B. Hayes

, as the representative of

sound money

, in the

Ohio

governor's campaign.

Interior Secretary

In 1876, he supported Hayes for President, and Hayes named him

Secretary of the Interior

, following much of his advice in other cabinet appointments and in his inaugural address. In this department, Schurz put in force his theories in regard to merit in the

Civil Service

, permitting no removals except for cause, and requiring competitive examinations for candidates for clerkships. His efforts to remove political patronage met with limited success. As an early conservationist, he prosecuted land thieves and attracted public attention to the necessity of forest preservation.

During Schurz's tenure as Secretary of the Interior, there was a movement, strongly supported by Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman, to transfer the

Office of Indian Affairs

to the

War Department

.

[10]

Restoration of the Indian Office to the War Department, which was anxious to regain control in order to continue its "pacification" program, was opposed by Schurz, and ultimately the Indian Office remained in the Interior Department. The Indian Office had been the most corrupt of the Interior Department. Positions there were based on political patronage and seen as granting license to use the reservations for personal enrichment. Schurz realized that the service would have to be cleansed of corruption before anything positive could be accomplished, so he instituted a wide-scale inspection of the service, dismissed several officials, and began civil service reforms, where positions and promotions were based on merit, not political patronage.

[11]

Schurz's leadership of the Indian Affairs Office was not uncontroversial. While certainly not an architect of the campaign to push Native Americans off their lands and into tribal reservations, Schurz continued the previous practice of the Bureau of Indian Affairs of resettling tribes on reservations. In response to several nineteenth century reformers, however, Schurz later rescinded his approval of the policy of removing Indians from their homelands, promoting assimilationist policies that were in favor among reformers at the time.

[12]

[13]

New York City

Upon leaving the Interior Department in 1881, Schurz moved to

New York City

. That year

Henry Villard

acquired the

New York Evening Post

and

The Nation

and turned the management over to Schurz,

Horace White

and

Edwin L. Godkin

.

[15]

Schurz left the

Post

in the autumn of 1883 because of differences over editorial policies regarding corporations and their employees.

[16]

In 1884, he was a leader in the Independent (or

Mugwump

) movement against the nomination of

James Blaine

for president and for the election of

Grover Cleveland

. From 1888 to 1892, he was general American representative of the

Hamburg American Steamship Company

. In 1892, he succeeded

George William Curtis

as president of the

National Civil Service Reform League

and held this office until 1901. He also succeeded Curtis as editorial writer for

Harper's Weekly

in 1892 and held this position until 1898. In 1895 he spoke for the Fusion anti-

Tammany Hall

ticket in New York City. He opposed

William Jennings Bryan

for

president in 1896

, speaking for sound money and not under the auspices of the Republican party; he supported Bryan

four years later

because of anti-

imperialism

beliefs, which also led to his membership in the

American Anti-Imperialist League

. At the age of 69, Schurz and other Mugwumps, lobbied President

McKinley

to resist imperialism and not to annex

Cuba

during the

Spanish American War

.

[17]

Schurz argued later racially that culture and languages of

Spanish creole

and

Africans

would corrupt American politics; enabling Spanish-Americans to elect

U.S. Presidents

.

[17]

In the 1904 election

he supported

Alton B. Parker

, the Democratic candidate. Carl Schurz lived in a summer cottage in Northwest Bay on Lake George, New York which was built by his good friend

Abraham Jacobi

. Schurz died in New York City and is buried in

Sleepy Hollow Cemetery

,

Sleepy Hollow, New York

.

German-American identity

Schurz maintained a relationship with the German

expatriate

community. He addressed a group of German immigrants at the

Chicago World's Fair

in 1893:

I have said: who does not honor the old fatherland is not worthy of the new, but I say also he is not worthy of the old fatherland who is not one of the most faithful citizens of the new.

Noblesse oblige

. To be a German now means more than it meant before he belonged to one united nation. He who calls himself a German now must never forget his honorable obligation to his name; he must honor Germany in himself. The German-American can accomplish great things for the development of the great composite nation of the new world, if in his works and deeds he combines and welds the best that is in the German character with the best that is in the American. — Carl Schurz,

German Day

, June 15, 1893.

"The True Americanism"

What is the rule of honor to be observed by a power so strongly and so advantageously situated as this Republic is? Of course I do not expect it meekly to pocket real insults if they should be offered to it. But, surely, it should not, as our boyish

jingoes

wish it to do, swagger about among the nations of the world, with a chip on its shoulder, shaking its fist in everybody's face. Of course, it should not tamely submit to real encroachments upon its rights. But, surely, it should not, whenever its own notions of right or interest collide with the notions of others, fall into hysterics and act as if it really feared for its own security and its very independence. As a true gentleman, conscious of his strength and his dignity, it should be slow to take offense. In its dealings with other nations it should have scrupulous regard, not only for their rights, but also for their self-respect. With all its latent resources for war, it should be the great peace power of the world. It should never forget what a proud privilege and what an inestimable blessing it is not to need and not to have big armies or navies to support. It should seek to influence mankind, not by heavy artillery, but by good example and wise counsel. It should see its highest glory, not in battles won, but in wars prevented. It should be so invariably just and fair, so trustworthy, so good tempered, so conciliatory, that other nations would instinctively turn to it as their mutual friend and the natural adjuster of their differences, thus making it the greatest preserver of the world's peace. This is not a mere idealistic fancy. It is the natural position of this great republic among the nations of the earth. It is its noblest vocation, and it will be a glorious day for the United States when the good sense and the self-respect of the American people see in this their "manifest destiny." It all rests upon peace. Is not this peace with honor? There has, of late, been much loose speech about "Americanism." Is not this good Americanism? It is surely today the Americanism of those who love their country most. And I fervently hope that it will be and ever remain the Americanism of our children and our children's children.

—

Carl Schurz,

"

The True Americanism

", address delivered in New York City at a meeting of the Chamber of Commerce of the State of New York, January 2, 1896.

Patriotism

The man who in times of popular excitement boldly and unflinchingly resists hot-tempered clamor for an unnecessary war, and thus exposes himself to the opprobrious imputation of a lack of patriotism or of courage, to the end of saving his country from a great calamity, is, as to "loving and faithfully serving his country," at least as good a patriot as the hero of the most daring feat of arms, and a far better one than those who, with an ostentatious pretense of superior patriotism, cry for war before it is needed, especially if then they let others do the fighting.

—

Carl Schurz,

"

About Patriotism

", Harper’s Weekly, April 16, 1898.

Publications

Schurz published a number of writings, including a volume of speeches (1865), a two-volume biography of

Henry Clay

(1887), essays on Abraham Lincoln (1899) and

Charles Sumner

(posthumous, 1951), and his

Reminiscences

(posthumous, 1907–09). His later years were spent writing the memoirs recorded in his

Reminiscences

which he was not able to finish — he only reached the beginnings of his U.S. Senate career.

In memoriam

Schurz is memorialized in numerous places around the United States:

Carl Schurz Park

, a 14.9 acre (60,000 m²) park in

New York City

, adjacent to

Yorkville, Manhattan

, overlooking the waters of

Hell Gate

. Named for Schurz in 1910, it is the site of

Gracie Mansion

, the residence of the

Mayor of New York

since 1942

Karl Bitter

's 1913 monument to Schurz outside

Morningside Park

, at Morningside Drive and 116th Street in New York City

Carl Schurz and Abraham Jacobi Memorial Park in

Bolton Landing, New York

Schurz, Nevada

named after him

Carl Schurz Drive, a residential street in the northern end of his former home of

Watertown, Wisconsin

Schurz Elementary School, in

Watertown, Wisconsin

Carl Schurz Park

, a private membership park in Stone Bank

(Town of Merton)

, Wisconsin, on the shore of Moose Lake

Schurz Monument ("Our Greatest German American") in Menominee Park,

Oshkosh, Wisconsin

[1]

Carl Schurz High School

, a historic landmark in

Chicago

, built in 1910.

Schurz Hall, a student residence at the

University of Missouri

.

Carl Schurz Elementary School in

New Braunfels, Texas

Mount Schurz

, a mountain in eastern Yellowstone, north of

Eagle Peak

and south of Atkins Peak, named in 1885 by the

United States Geological Survey

, to honor Schurz's commitment to protecting

Yellowstone National Park

In 1983, the U.S. Postal Service issued a 4-cent

Great Americans series

postage stamp with his name and face

In World War II, the United States

liberty ship

SS

Carl Schurz

was named in his honor.

The

USS

Carl Schurz

was commissioned in 1917 as a Patrol Gun Boat. Formerly the small unprotected cruiser

SMS

Geier

of the German Imperial Navy, the ship had been taken over by the U.S. Navy when hostilities between Germany and the U.S. commenced, after having been interned in Honolulu in 1914. The

Schurz

sank after a collision in April 1918 off Beaufort Inlet, Florida.

Several memorials in

Germany

also commemorate the life and work of Schurz:

Streets named after him in

Berlin-Spandau

,

Bremen

,

Stuttgart

,

Erftstadt-Liblar

,

Giessen

,

Heidelberg

,

Karlsruhe

,

Köln

,

Rastatt

,

Paderborn

,

Pforzheim

,

Pirmasens

,

Leipzig

,

Wuppertal

Schools in

Bonn

,

Bremen

,

Berlin-Spandau

,

Frankfurt am Main

,

Rastatt

and his place of birth,

Erftstadt-Liblar

The Carl Schurz Haus in

Freiburg im Breisgau

is an innovative institute (formerly Amerika-Haus) fostering German-American cultural relations

an urban area in

Frankfurt am Main

the Carl Schurz Bridge over the

Neckar River

[2]

a memorial fountain as well as the house where Lt. Schurz was billeted in 1849 in

Rastatt

German Armed Forces barracks in

Hardheim

German federal stamps in 1952 and 1976

The

United States Army

base in

Bremerhaven

, Germany was also named for Schurz - Karl Schurz Kaserne. The base served as a logistical hub for U.S. forces in Germany. The

base

was returned to the German government in 1996, following the end of the

Cold War

.

Schurz was portrayed by

Edward G. Robinson

in

John Ford

's film

Cheyenne Autumn

(1963), which shows in part his efforts to secure fair treatment for Native Americans.

Highlights of Schurz's career are dramatized in the third part (“Little Germanies”) of Engstfeld Film's four-part series

Germans in America

(2006).

[18]

Notes

1.

Wisconsin Historical Society: Schurz, Carl 1829 - 1906

2.

Schurz, Margarethe [Meyer] (Mrs. Carl Schurz) 1833 - 1876

3.

"Nation's Orators Glorify Schurz; Carnegie Hall Memorial a People's Tribute. Country Needs Such Men; Chairman Choate Rebukes New York Senators -- Cleveland, Eliot and Others Speak,"

New York Times.

November 22, 1906. These tributes are available in Wikisource at

Addresses in Memory of Carl Schurz

.

4.

Schurz, Carl, remarks in the Senate, February 29, 1872,

The Congressional Globe

, vol. 45, p. 1287. See

Wikisource

for the complete speech.

5.

Schurz, Carl.

Reminiscences

, Vol. 1, pp. 93-94.

6.

Van Cleve, Charles L. (1902).

Phi Kappa Psi Fraternity From Its Foundation In 1852 To Its Fiftieth Anniversary

. p. 209

: Philadelphia: Franklin Printing Company.

7.

Schurz,

Reminiscences

, Vol. 1, Chap. 6, pp. 159.

8.

Hirschhorn, p. 1713.

9.

This story, and the conflict between Nast and Harper's editorial writer George William Curtis, is related by Albert Bigelow Paine in

Thomas Nast: His Period and His Pictures

, 1904.

10.

"Army charges answered"

.

The New York Times

: 5. December 7, 1878. "ARMY CHARGES ANSWERED; THE INDIAN SERVICE UPHELD BY MR. SCHURZ. WHY IT WOULD BE UNWISE TO TRANSFER THE INDIAN BUREAU TO THE WAR DEPARTMENT--INCONSISTENT AND INACCURATE STATEMENTS BY MILITARY OFFICERS--LOOSE MANAGEMENT UNDER THE ARMY. INCONSISTENT AND INACCURATE STATEMENTS BY ARMY OFFICERS. ALLEGED ARMY DISHONESTY. MEASURES OF IMPORTANCE. MR. SCHURZ CROSS-EXAMINED. OTHER WITNESSES"

11.

Trefousse, Hans L.,

Carl Schurz: A Biography

, (U. of Tenn. Press, 1982)

12.

Hoxie, Frederick E.

A Final Promise: The Campaign to Assimilate the Indians, 1880-1920,

Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1981.

13.

"Annual Report of the Secretary of the Interior, November 1, 1880," In Prucha, Francis Paul, ed.,

Documents of United States Indian Policy,

Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2000. See

Google Books

.

14.

Sturm und Drang Over a Memorial to Heinrich Heine

.

The New York Times

, May 27, 2007.

15.

Oswald Garrison Villard

(1936). "White, Horace".

Dictionary of American Biography

. New York:

Charles Scribner's Sons

.

16.

“

No Longer an Editor; Carl Schurz Severs his Connection with the 'Evening Post'

.”

The New York Times

, December 11, 1883

17.

Tucker (1998), p. 114

18.

"Germans in America"

. Engstfeld Filmproduktion

. Retrieved 14 April 2011

.

See the accompanying press photos. A photo from the Schurz dramatizations appears in the photos for the second part (“The Price of Freedom”), but at least in a DVD viewing of 10 April 2011 the bulk of the dramatizations appeared in the third part.

I am a proud member of the Universal Autograph Collectors Club (UACC), The Ephemera Society of America, the Manuscript Society and the American Political Items Collectors (APIC) (member name: John Lissandrello). I subscribe to each organizations' code of ethics and authenticity is guaranteed. ~Providing quality service and historical memorabilia online for over twenty years.~

WE ONLY SELL GENUINE ITEMS, i.e., NO REPRODUCTIONS, FAKES OR COPIES!